Vi har 5 bilder till som vi skall bearbeta, när vi hitta originalet.

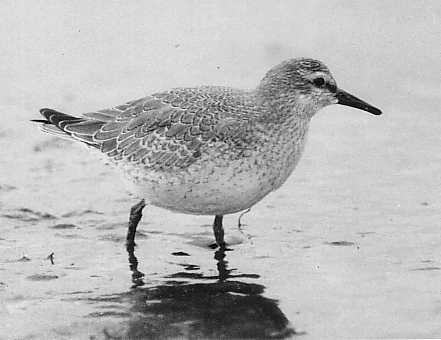

Då skärsnäppan oroas springer den gärna upp på en sten eller tuva uppmanande att ungarna skall trycka Luottolakto 1943

English summary FoF 1945

On the presence o f the Purple Sand piper, Calidris m. maritima,

in the Swedish high mountains and its breeding biology.

Up till 1933 the Purple Sandpiper had only once been found breeding in Sweden.

Now it is known as regularly breeding in the high mountains in southwest

Jämtland, and, in 1939, its nest was found on Mount Sjaule in northwest

Jämtland. In Lapland it was found in 1938 living on Ammarfjället, and in the

Plain of Råtakvagge - Vuorekjaure, there are at least 25 pairs. Nests and chicks

have been found on Svaipa and Kirjastjåkko. And on the plateau of Luottolako,

about 1 300 m high, in the National Park of Sarek, 14 pairs were counted living

in 1943. That, with a single exception, this list of discoveries has been

obtained from 1933 or latar, does, however, certainly not depend on the fact

that the species was earlier missing in our country and has only recently

settled down there, but that it was overlooked on account of its habit of living

in very desolate and seldom visited plains of high mountains, where, besides, it

lives quietly and is not easily discovered. Thus there is no doubt that in 1903

it was found in about the same extent as now on Luottolako, although the species

was then mistaken for Calidris alpina.

The biotope of the Swedish high mountains principally consists of extended

plateaus 1000-1400 m high with mostly naked, often very stony, usually damp, but

not wet tundra ground in the neighbourhood of small lakes. In these plains there

are during a great part of summer large surfaces strained through by melting

water from adjacent snow fields.

From museums and private collections in Scandinavia the following specifications

of size have been obtained.

For 66 males: length of bill 23,5-34 mm, average 28,0. 7,6% have length of bill

over 30,0 mm. Length of wings on an average 124,3 mm. For 56 females: bill

26,2-37,0, average 32,4 mm. 83,9 % have length of bill over 30,0 mm. Wings on an

average 128,5 mm.

The possibility of finding a male mated with a more brevirostral female is not

very great. Male has also a proportionally shorter bill. The length of males

bill stands to the length of wings as 22,6: 100, while the corresponding

relation for female is 25,2: 100.

In the fields, during the time of breeding, you will see that female has a

darker grey ground-color on her throat and breast than males. In many cases male

has not got the well-known orange-colored spot on the base part of the upper

bill.

At the eggs the Purple Sandpiper is almost as trustful as Eudromias morinellus

and soon learns to return to its eggs, even if you remain sitting a couple of

meters from the nest.

Display multiform, not bound to any certain ritual. Usually beginning by the

mates running after each other in the furrows of the ground, in doing which one

or both have one wing stretched straight up in the air (''wing ceremony''). At

this often prolonged cries. Then the courtship flight, which may be a chief

moment in display: both birds take flight, evidently male first, at times only

male, and fly near the ground in long curves (several 100 m) up over the

breeding grounds or out over ices and snow fields. The carriage of wings shifts

more than with most other waders. Sometimes ecstasy begins to find expression in

the wings being taken in a whirring swift pace only above the horizontal plane

in the manner that is characteristic of the display-flight of Calidris

temminckii, then follows a long stretch of gliding flight, most usually with the

wings stiffly curved in an obliquely upwards directed position, and the gliding

flight is now and then interrupted by a few prompting wing-beates. Sometimes it

is done with the wings in a stiff curve downwards as with Actitis hypoleucos.

The Purple Sandpiper may also be seen flying like a posturing Charadrius

hiaticula or C. apricarius with the peculiar stiff, slow wing-strokes of these,

while the bird turns over now on one, now on the other side. During the display

flight a far ringing cry is heard, which is rendered ''ter-ter-terpree-pree-preeo''.

Even a young one a week old did the »wing ceremony», when it, frightened, ran

away after being marked with a ring.

Cock nests have been observed even in the Swedish high mountains. The nest

proper is normally a shallow pit, mainly lined with dry last year's leaves of

Salix herbacea or polaris.

16 eggs from the plain round Vuorekjaure, July 1944, measured on an average 35,7

x 26,0 mm. The number of eggs is oftenest 4, but also 3 may be considered

normal. In 1942 the author saw 2 nests with 3 eggs each, in 1943 3 nests with 3,

3, 4 eggs respectively, and in 1944 4 nests with 4 eggs in each.

Incubation begins in summers with normal weather mostly about 12-20 of June. At

belated snow melting, however, much later, sometimes not until in July. The

rather thickly inhabited plain of Vuorek was, on June 16th 1944, covered with

deep snow up to 95%. There most of the Purple Sandpipers began to sit about June

28th, when the larger part of the plain was free from snow.

Both mates take considerable part in incubation. Different pairs divide this

work differently, but the birds succeed each other only one or two times a day.

At a nest in 1942 the sitting female was watched from a photographer's tent near

the nest. She left it only after 12 3/4 hours of watching, when, at 4.02 o'clock

at night, she was succeeded by male, and male was still lying on the nest, when,

after another 17 1/3 hours, the author left him. - In 1944 a nest was

uninterruptedly watched for more than two days and nigths, 1944-07-07--07-09.

The eggs had then been incubated for a little more than a week. Male sat for 14

½ hours, female then for 17 ½, male again for 14 2/3. Female was then still

sitting after 15 ½ hours, when the watching ceased. At a nest near by, which had

eggs just as long incubated and could be controlled every two hours, two

successive periods of sitting were established for male = 16 3/4-18 ½, for

female = 11-13 hours.

The bird not sitting generally stays far from the nest and has very little

contact with the sitting bird. On the 1942-07-04 at 16 o'clock, a female had

been frightened away from the nest by a dog. She did not return (possibly lost),

and still on the morning of the 07-05 at 2.30, the eggs were cold. Later male

was observed sitting on the eggs, but the observation indicates that during the

time of 16-2.30 o'clock, that is to say for at least 10 1/2 hours, he was

ignorant of female having left the eggs.

Incubation period unknown. An investigation of the literature in the matter

shows that all statements of the time of sitting on the eggs published up till

now have been founded on quite theoretical and uncertain primary statements.

Those not brooding have usually every one their feeding area. Seldom do those in

the Swedish high mountains gather to common feeding areas, if ice and snow

circumstances do not force them to do so.

In most cases only one bird seems to take care of the young ones, and when the

sex can have been verified, it has been a in these cases. The behaviour of the

birds is quite changed after the hatching of the eggs. Previously the sitting

bird sat close till you were so near, that you almost trampled on it, and then

tried to allure the peacebreaker from the nest by artifices. After the young

ones are taken away from the nest, the watching old bird reveals its presence by

a laughing »kryhihihihi» and other sounds even at a distance of 30-40 m and

shows itself openly and without feighning injury.

The Purple Sandpiper seeks its food mostly on the stony shore of small mountain

lakes or on ground traversed by melting water. It sometimes also will bore with

its bill under the shore tufts or in the sand on a smooth sandy shore. Like

Plectrophenax and others it likes to pick the insects that often lie in great

numbers numb in the snow fields in the height of summer.

Bo av Mosnäppa

Foto Holger Johansson Skara.

Det framgår inte

var han tagit dessa bilder.

Det framgår inte

var han tagit dessa bilder.

Although much has been discovered in recent years about the lives of Palearctic waders, that of the Broad-billed Sandpiper (Limicola falcinellus) is still largely a mystery. It occurs in most parts of Europe and Asia, but neither its summer nor its winter range has been fully worked out, and very little is yet known about its breeding biology. Its obscurity seems to be due mainly to its secretive behaviour in the breeding season, and to its allegedly nondescript appearance in winter plumage. However this species is quite distinctive in the field, and there seems no reason why it should not become better known.

It is known to breed over much of Scandinavia, from arctic Norway and Finland south to the mountain bogs of southern Norway and central Sweden. To the east, it is thought to breed right across European Russia and Siberia to the Pacific coast, but this presumption is based entirely on records in winter and on passage, and there is not one definite breeding record from the whole of this vast area!

The broad-billed Sandpiper is an odd looking bird, as large as the smallest of Dunlins (Calidris alpina), but with proportionately shorter legs and with a bill which would look long even on a large Dunlin. The shape of the bill is distinctive, rather heavy at the base and with a noticeable downward kink towards the tip. This long heavy bill, on a bird scarcely larger than a Little Stint (C. minuta), gives it a squat, ungainly appearance, which is only slightly relieved by its active feeding habits. In breeding plumage, adults are completely unmistakable, having a strikingly striped head and blackish upper-parts with rich buff longitudinal stripes. As many text-books point out, this plumage is superficially like that of a Jack Snipe (Lymnocryptes minimus), but in fact there is little danger of confusion with that species, since the general shape and appearance of the bird suggest a Dunlin or Little Stint. In winter plumage adults are grey above and white below and look much like Dunlins, but the stripes on the head are still conspicuous and unmistakable.

These markings consist of a white superciliary stripe separated by a narrow dark line from a second white stripe on the side of the crown. In the birds shown in the plates the dark line runs forward almost to the bill. Immatures on autumn migration (in August and September) look much like summer adults, but the breast and eyestripes are suffused with buff, and the upper-parts are patterned in chequers of dark brown and buff. In flight the species shows less wing-bar than a Dunlin (sometimes none at all), but much white on the sides of the tail-coverts. The flight-note, unmistakable when known, is a dry chr-r-r-reet. This note and the double eyestripe are the best characters of the species in all plumages.

Very little seems to have been published on the breeding of the Broad-billed Sandpiper since the scanty notes in The Handbook (1940), although it has been photographed at the nest several times.

It breeds secretively in quaking bogs, hiding its nest in tussocks of vegetation surrounded by treacherous semi-liquid mud; several pairs may be found together.

The present photographs of the Spotted Redshank (Tringa erythropus) are the first of a long series of remarkable photographs of Scandinavian breeding birds - most of them species occurring with more or less regularity in this country - by Swedish and Danish ornithologists, which we have been fortunate in securing for reproduction in British Birds.

The Spotted or Dusky Redshank is one of the characteristic breeding birds of swamps in or close to the forest belt of Northern Europe and Asia and occurs in this country not uncommonly on passage and more rarely in winter. The name Spotted Redshank was no doubt primarily suggested by the appearance of the young birds in autumn, while the alternative one has reference to the breeding plumage.

Male on nest.

Male on nest.  the nest itself

the nest itself The latter, is very striking and quite exceptional amongst waders of the sandpiper type in being predominantly black or blackish. In autumn and winter the appearance is less remarkable, but the species is easily distinguished from the Common Redshank both by visual characteristics and by the highly distinctive note, "tchu-et" or "tchu-e," which lacks the whistling musical quality of the Redshank's and is very easy to recognize when once known: In appearance the bird is rather larger than the Common Redshank, with somewhat longer legs and bill. The plumage in general is greyer, but the most obvious feature is the lack of the prominent white on the secondaries when the bird takes to flight. The young birds in autumn have the upper-parts notably more spotted and streaked in appearance than the old ones, in which the mantle is a more uniform grey.

Mr. Swanberg's photographs of the breeding bird and nest were all taken on a large swamp with a few scattered pines in a pine forest area near Arjeplog in Lapland.

The figure illustrates the habit common to many of the northern waders of perching freely on trees in the breeding-season.

The Green Sandpiper (Tringa ochropus) is, after the common species such as Common Sandpiper and Dunlin, probably the most familiar of the passage waders occurring in inland localities in Britain, where its strikingly black and white appearance on the wing make it easy to recognize.

It has a wide breeding distribution in northern, north-central, and eastern Europe and ranges right across Asia. As is well known, it usually breeds in old nests of other birds and Mr. Swanberg's photographs taken in spruce forest in Middle Sweden show a bird and eggs in an old nest of the Song-Thrush (Turdus ericetorum). The photographs were taken 1946, but Mr. Swanberg informs us that this is an abnormal date, the species usually having fresh eggs in Sweden in late April or early May and up till mid-May. It will be noticed that the ,eggs, one of which is a dwarf specimen, are lying on a considerable bed of lichens, moss and some bents, torn away by the bird from the outside of the nest. The nest was examined on June 9th before the eggs were laid and then contained only a few lichens. Mr. Swanberg informs us that in the case of two other clutches examined in Song-Thrush's nests in 1945, the bird had made a similiar bed for the eggs, though not so heavy as in the present

case.

Hanne 1960

Hanne 1960

Bo av Myrspoven.